Jarom Vogel is an illustrator and digital artist from the BYU Illustration program. Although an aspiring dentist, he will not be following in the small footsteps of Hermey the Elf. He lives in Utah.

Tell us how you became an artist. I’ve always liked drawing – I think my earliest memories of it would be drawing during church (I’m sure I’m not alone in this on this site). I took art classes in junior high and high school and they were always some of my favorite classes. People seemed to think I was good at it (although looking back at some of that stuff, I’m not really sure why). I actually started out at BYU doing pre-dental courses and just took a few illustration classes on the side because I thought they would be fun. Gradually I ended up declaring an illustration major, got into the BFA program, and somewhere along the line decided I would hate being a dentist and gave up on that.

What do you think about ‘Mormon Art’? I have mixed feelings on this – on the one hand, I love the idea of my culture, heritage, background etc. informing my art. I mean, that’s a part of who I am, and I want that to show through in my artwork. On the other hand, I don’t really like the idea of being labeled as a ‘Mormon Artist’ because it seems like that limits what kind of work people expect from me. Not that I’m opposed to doing religious work – I would be really interested in exploring that at some point – I just don’t like the idea of always coming from that angle. I think it works really well for some people, but it’s probably not my thing. So I love the idea of Mormon artists, and I don’t think we should shy away from letting people know who we are, but I also don’t think that needs to define our artwork.

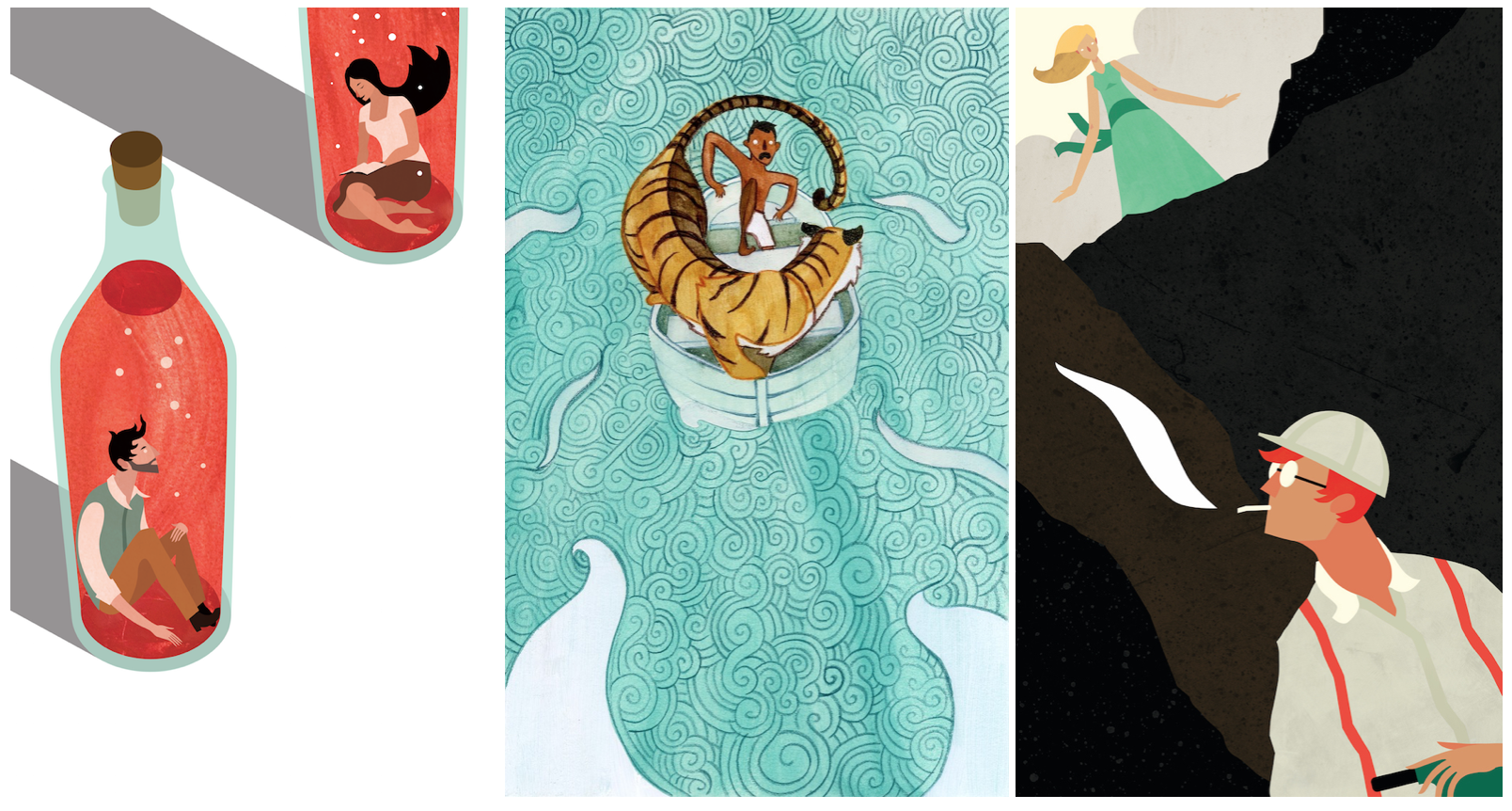

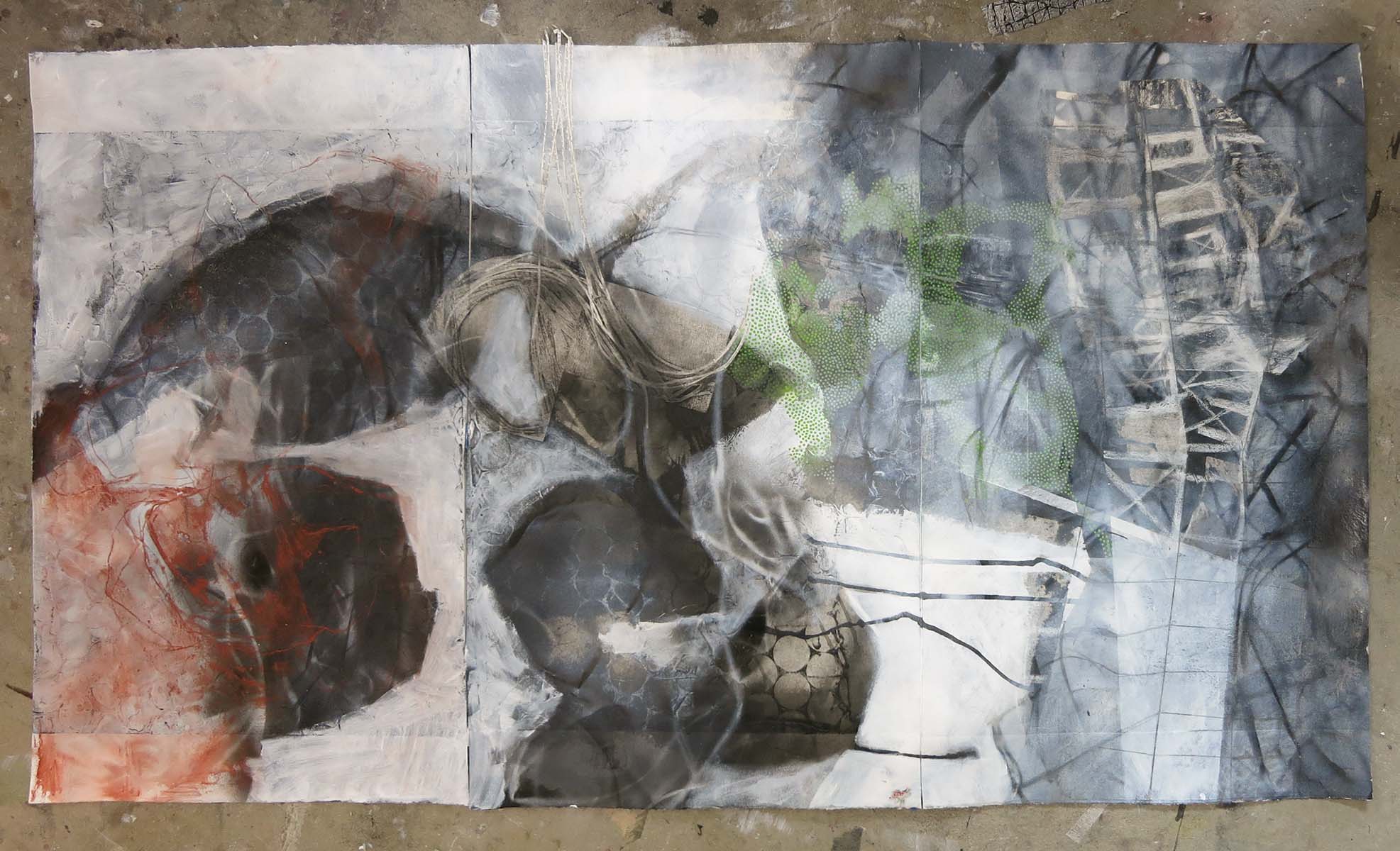

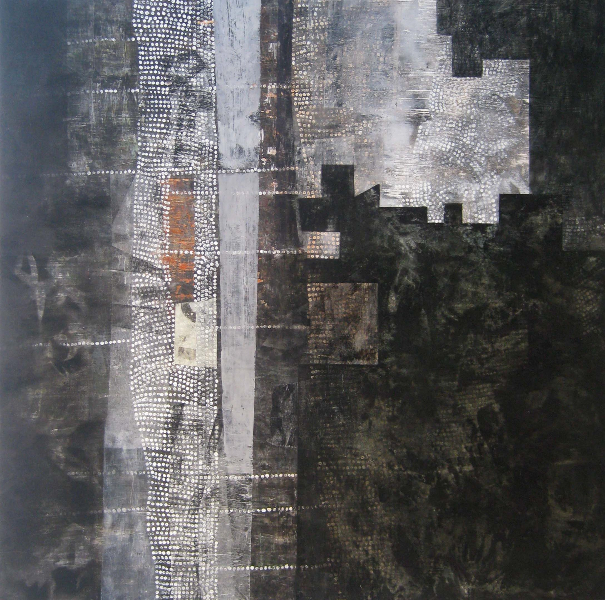

Talk about your Phantom Tollbooth project (set in India). I really love working with traditional paint media, but I’m also kind of a huge computer nerd so I end up doing a lot of digital work. The Phantom Tollbooth project was meant as a way to blend the feeling of acrylic paints with the benefits of digital art (below). I think there’s a certain impact of art that you lose when you move from traditional to digital, so the motion part was a way to try and compensate for that. You lose some color and vibrancy, but you gain motion, interactivity, things like that. I don’t know how successful it was in that sense, but it was fun to do. I had never really done anything with motion before, so it was a really great learning experience. The subject matter, the Phantom Tollbooth, is a book that I’ve loved since I was a kid and just wanted to do something with it. If anybody hasn’t read it, you really should. It’s super clever and funny.

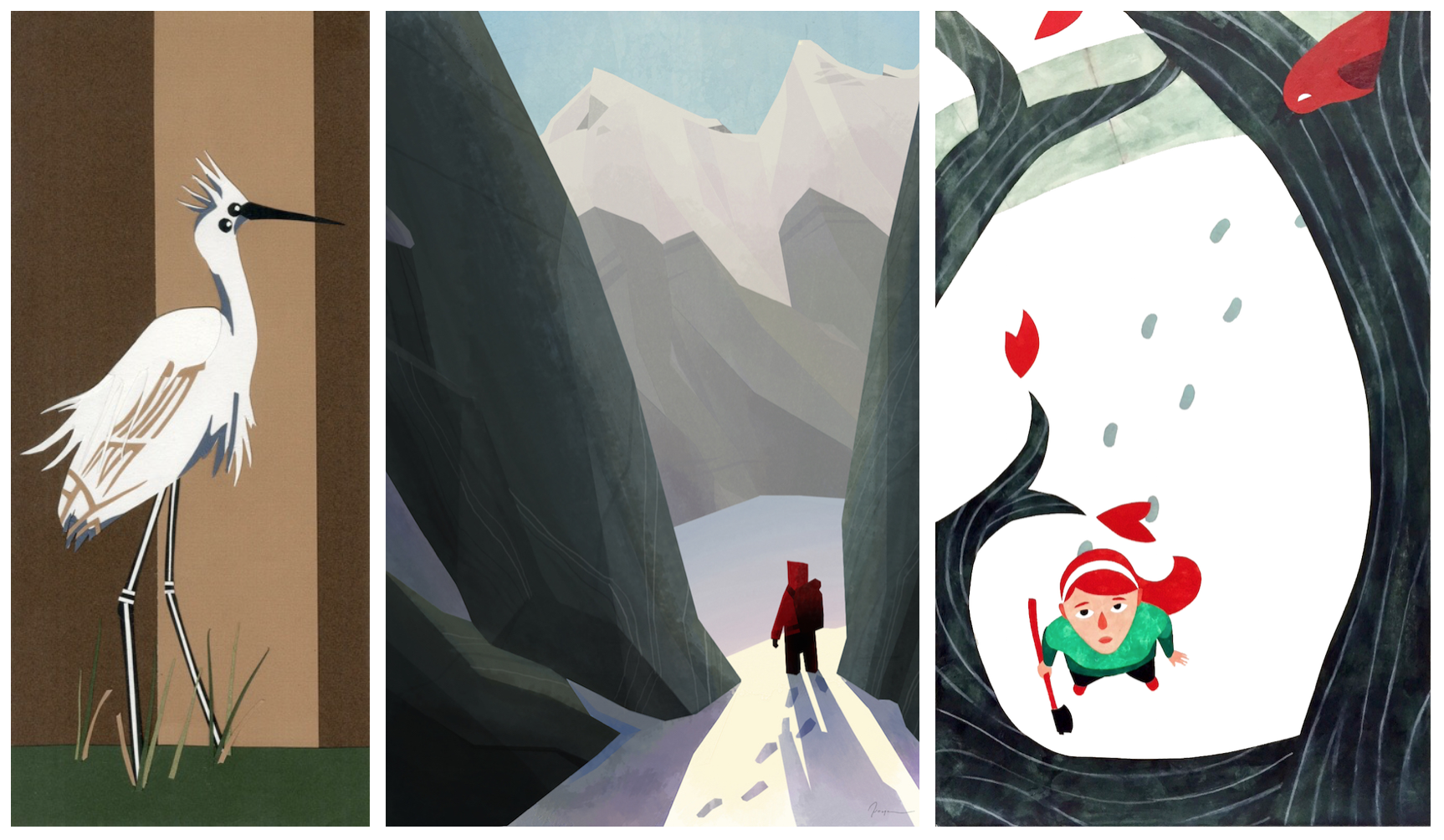

What are you working on next? I’m really good at starting projects and not finishing them, so I have a few different projects kicking around that maybe I’ll finish someday. I’m currently working on a stop motion project with some people (Trisha Zemp, Spencer Bugg, Ginger Dall, Madeline McKell and Chelsea Dalton – all very talented people). It’s a cut paper thing and is going to be really cool. That should hopefully be done by the end of the year. I’ve also been playing with the idea of making a children’s book app with some interactive illustrations and have a few bits and pieces of that floating around. I haven’t done much actual painting since graduating, so I’d really like to spend time getting some cadmium on my hands again.