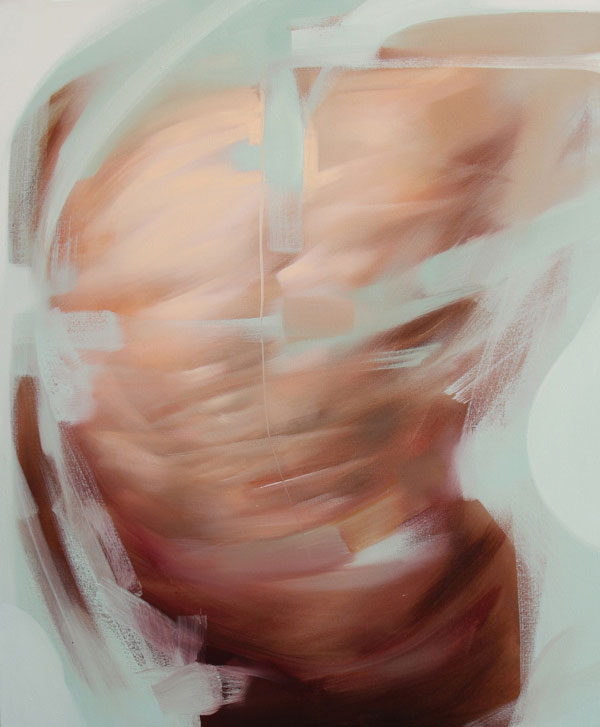

Ryan Muldowney is a teacher, painter, and creator and is currently an assistant professor of studio arts. These images come from his two series unravled I and unraveled II. Muldowney received a BFA from The University of the Arts in Philadelphia and an MFA from The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. He lives in Virginia with his family and has also had works of fiction and non-fiction published.

How would you describe yourself as an artist? I am something of an artistic omnivore. My interests in art are various and I like to allow myself the freedom to explore any and all avenues of creation in the execution of my work. As a young artist I would often hear to my chagrin that it was important to consolidate your interests and develop a characteristic style, but this never sat well with me as I was unwilling to lay aside the sometimes-incongruous battery of artistic interests that continually held my attention. To this day I have never yet been able to settle down, and every time I stumble across something new that I like, I do it over and over again, refining and experimenting until the body of work no longer holds any mystery for me and then I move on to the next thing. I guess “mystery” is pretty fundamental to my work and to my process. I don’t like to be too facile or familiar with my materials because I hope that the work will reflect my uncertainty and thus open a doorway for the viewer to enter and to create enough room, hopefully, to wonder. I don’t wish for everything to be said or explicitly described, I don’t want the experience of viewing the work to be easy. Work that has that sense of mystery demands interaction, and I feel that although my studio habits may deny me a signature style, having a rambling practice creates infinite opportunities to examine the unknown.

You are what I would call an ‘East Coast Mormon’. Do you feel like you have a different perspective than many of the Utah-based Mormon artists? I don’t know that I have had many personal interactions with Utah-based Mormon artists, so I couldn’t rightly say how my perspective might be different. But it occurs to me, (and it may be an over-generalization) that the culture of the mountain west has, as far as I have been able to observe, a profound interest in the kind of professional “success” that is categorized by financial remuneration. Many of the Utah-based Mormon artists that I have observed from afar appear to have been the product of this cultural interest in financial “success”, and this seems to influence the kind of work that they make. Their work is often finely attuned to market forces. I say this not as a value judgment but merely as an observation of how my perspective may be different. I only ever make what I want to make, and I always make it with the full knowledge that I will soon be packing the work into storage when it is done, that few people will ever see it, and that the cost of materials, framing, etc. are a dead loss from a financial point of view. While this is clearly an impractical enterprise, I find that the compensations of absolute freedom are not inconsiderable.

Teaching has been a big part of your career. How has teaching affected your own development as an artist? So much in art is intuitive and too often critical aspects of the act of creation are not easily transmissible because it is difficult to fitly describe the experience. For me, therefore, teaching becomes an invaluable tool because it compels me to not be satisfied in understanding my practice merely by intuition, but to strive very hard to make the experience communicable in language so that others may begin to understand it as well. Staging projects that will most effectively draw out this understanding becomes essential and I do a great deal of experimentation in my own studio in an effort to transmit understanding of these difficult ideas. Thus, in striving to communicate the incommunicable not only are my students lifted, but I find myself enriched with new tools and processes that I can then use in my own work. There is a nice kind of symbiosis to that kind of relationship, and I value it deeply.

You once wrote, “I seek for mastery, not of process but of understanding.” I see mastery as one of the most important ideas to which we can cling in this life. It is an all-governing principle. I seek for mastery in all aspects of my life including my art. But I have unfortunately found mastering a process to be an unfulfilling shadow of true mastery. I have come to feel that possessing a superlative technique in painting or drawing or some other process is ultimately a dead-end as technical mastery only leads to the elimination of possible outcomes. I prefer to work inexpertly and with uncertainty so that by my struggle I may gain understanding of the intrinsic qualities of new tools and new materials, and by my experiments I create little worlds of possibility that are new to me and that allow me to understand a little more and see a little further into the darkness, into the great “mystery”. Mastery of understanding can only be purchased with the coin of inquiry, and I prefer a practice that is fundamentally questioning rather than being a master of process who can do nothing but make statements.