Joanna Cutri is a globetrotting painter (and popular yoga instructor). She was born and raised in Pasadena, California to parents from Argentina who were both converts to the LDS church. At age six she moved back to Argentina and then back again to Pasadena. She studied art in Cleveland; Salt Lake City; Cortona, Italy; and received a BFA from the University of Georgia. She then lived in Bali for ten years and just recently moved to Biarritz in the south of France with her French fashion designer fiancée. These paintings are from her series of the Zhangjiajie Mountains in China.

Tell us about your evolution as an artist. I’ve always been an artist. I was incredibly blessed and fortunate to have been able to attend the Los Angeles County High School for the Arts. I owe that school EVERYTHING. It completely changed my life. And after having lived in Bali for over 10 years being fully immersed in the culture and religion, it became absolutely clearly obvious that this has been my spirit for many lifetimes. I’m playing out my pre-ordained destiny. My calling and purpose as an artist is simply a manifestation in THIS lifetime. The Balinese are all proud artists, it is a highly respected and honored position, which they value and cultivate. In Bali I discovered the strength of my artistic voice, my worth and how important -crucial!- it is for me, for all artists, to continue on this path. Bali is like the ultimate playground for an artist. I had tons of space and tons of time, so size and quantity was no object in terms of canvas. Now living in France I’ve had to scale down a lot, my canvases are smaller and when the house is literally stacked up with art, I have to set a limit.

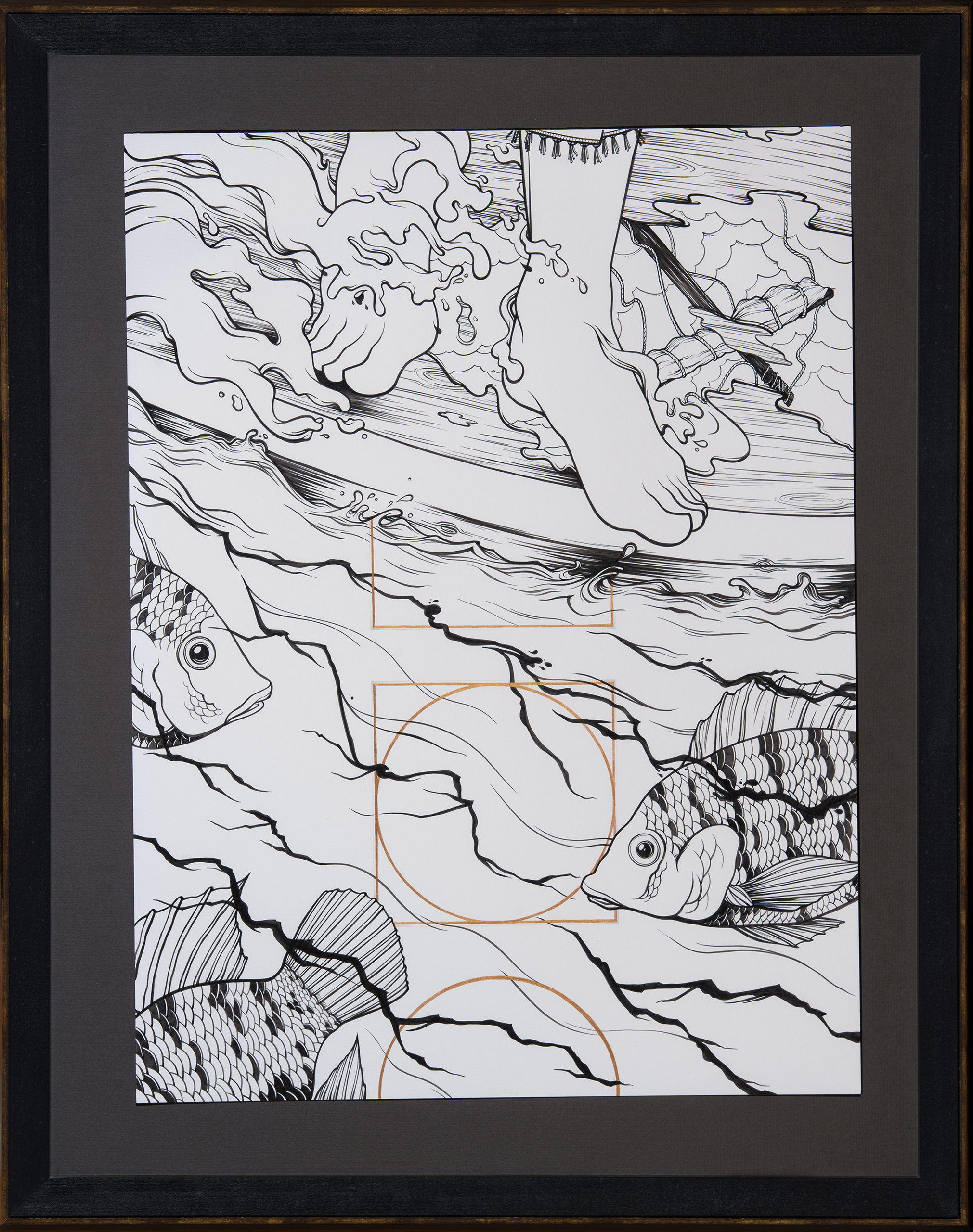

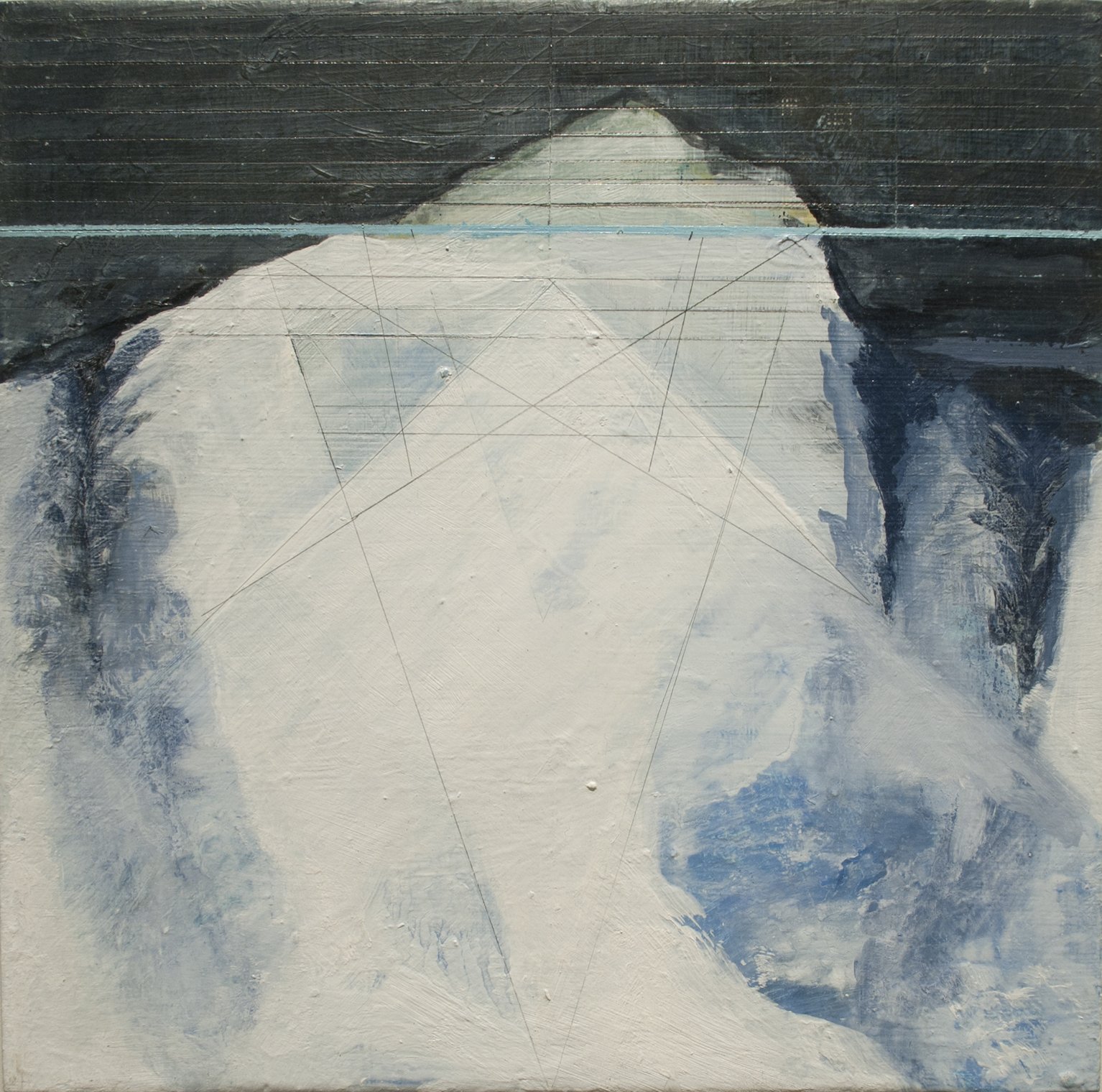

Creating art has always been this intense cathartic process. I never plan anything; I have absolutely no idea what is going to come out. It simply just happens. And most of the time at the end of a collection, I’m surprised wondering where it all came from. Spirit moves though me. It’s never an intellectual endeavor either. The approach and technical style of my paintings are always similar starting with collage. I love working with paper. My earliest memory at six years old is of shredding a newspaper into a million pieces and collaging it back together into this snow scene of a snowman family. I have a HUGE box of paper that I have been lugging around the world for years. Then my paintings are layers upon layers of mixed mediums. I’m a bit of a rebel when it comes to “painting”. With so much choice in diverse materials, I can’t imagine just using one, so I use them all. It’s an exploration of materials all left to chance. The concept or imagery always changes with each series. It usually reflects where I’m at in my life. My paintings are “landscapes” of my whole life. What has changed or evolved is the sense of urgency I feel now that I didn’t feel at 20. I feel like I haven’t created enough and that time is running out. I’m acutely aware that the time is NOW…or never. I either need to paint faster or find a way to expand time.

You’ve done a fair bit of globetrotting. Tell us how these travels have shaped your art. Traveling around the world is simply the way I live. I can’t seem to stay in one place for too long. It took me five years to finish my BFA after having gone to six different schools to get thru it. I have to see the world and live in different countries soaking it all in and then go hide in my studio and let it all come out. Every country has impacted my art. Every place has something special that causes me see things differently back in the studio. I’m the ultimate observer of my immediate surroundings, I notice everything, the most mundane details that most walk by and don’t pay attention to- like the texture of patterns on certain buildings in Paris that remind me of curly pasta, or shadows being projected on the sand in Krabi, Thailand by people dancing in front of party lights. Those discoveries and experiences while traveling are the answers to the creative problem solving process in the studio. They become a catalyst for wanting to recreate a characteristic on the canvas whether it be how to create a translucency like the light in Rote Island which is so crisp and clear or wanting to mix a perfect earth color like the vibrant land in Western Australia. It’s like taking the best part of my travels and not wanting to forget them, immortalizing them on my canvas. It’ s never obvious or so literal to the viewer, but all my travels are in my paintings one way or another.

You once said, “As an artist I need inspiration. I need stimulation.” Explain. I paint in solitude and to really get into creation mode I have always chosen places quite far removed, the makings of my own little bubble. After high school the obvious and easiest choice would have been to study art in LA or NYC like every person I went to school with, but I ended up living in Cortona, Italy which is a tiny Tuscan hill town virtually detached from anything. When I needed stimulation- people, museums, energy and a sensory overload of distractions, I would go to Florence 90 minutes away. Yet when I lived in the center of Milan, I rarely painted. Painting is a very solitary activity and being alone too much in the middle of nowhere like Bali can make you a bit loopy and claustrophobic. Being so isolated and in a very different reality to the Western world I had to travel extensively to absorb as much as I could, to fill my well of creativity. Back in my studio, I’m forced to dig deep into my own reservoir of inspiration and not be distracted by my immediate surroundings or by what is happening in popular culture or trend. I’m a huge contradiction; I can’t be living in chaos and create, I want to be out, be social and doing everything I possibly can, all at once. Yet when I’m creating, my world stops and I have to be alone and as far away as possible from any temptations of worldly delight. I can be incredible focused or totally ADD. Life is about contrast though…

What’s up next for you? I am en route to Hong Kong to present my latest collection to the Nock Art Foundation. In 2016 I hope to travel to various Asian Art Museums globally to share this experience as a lecture series and to exhibit this body of work. The premier viewing will be a selection of paintings shown at the Musee Asiatica here in Biarritz on January 9th. This has been a very interesting year full of change. I ended a decade in Bali with an artist in residency program in Hong Kong. I was chosen to participate in this cultural exchange of four Western artists painting the Zhangjiajie Mountains (the floating mountains of the movie Avatar) in the Hunan Province in China. It was an amazing experience. I’m not a plein air landscape artist at all and I was completely thrown out of my comfort zone on every level. On my own, I would have never gone to China to paint the most impressive landscape eight hours a day for seven days straight. It was really quite special and interesting to push the boundaries of creating in a completely new way. I ended up developing the collection in the south of France in Biarritz the last 8-9 months. These last few months have forced me to reflect on the severe contrast of east and west and how it relates and transpires in my work and in my life.